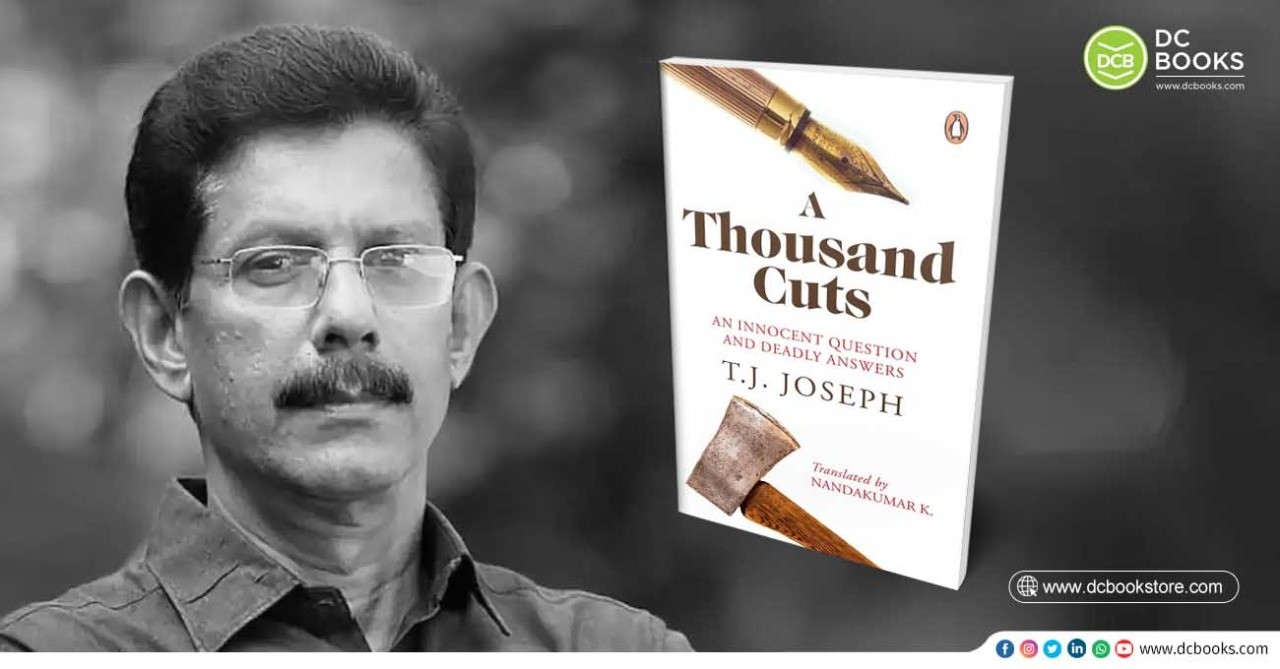

‘അറ്റുപോകാത്ത ഓര്മ്മകള്’; പ്രൊഫ. ടി.ജെ.ജോസഫിന്റെ ജീവിതത്തിലെ സമാനതകളില്ലാത്ത അനുഭവങ്ങള് ഓര്ത്തെടുക്കുന്ന ആത്മകഥ!

പ്രൊഫ.ടി.ജെ.ജോസഫിന്റെ ആത്മകഥ അറ്റുപോകാത്ത ഓര്മ്മകളുടെ’ ഇംഗ്ലീഷ് പരിഭാഷ ‘എ തൗസന്ഡ് കട്സ്-ആന് ഇന്നസെന്റ് ക്വസ്റ്റ്യന് ആന്ഡ് ഡെഡ്ലി ആന്സേഴ്സ്’ -ല് നിന്നും ഒരു ഭാഗം

ഡി സി ബുക്സ് പ്രസിദ്ധീകരിച്ച പ്രൊഫ.ടി.ജെ.ജോസഫിന്റെ ആത്മകഥ അറ്റുപോകാത്ത ഓര്മ്മകളുടെ’ ഇംഗ്ലീഷ് പരിഭാഷ ‘എ തൗസന്ഡ് കട്സ്-ആന് ഇന്നസെന്റ് ക്വസ്റ്റ്യന് ആന്ഡ് ഡെഡ്ലി ആന്സേഴ്സ്’ -ല് നിന്നും ഒരു ഭാഗം

26 March 2010. I was woken up from a disturbed sleep by the ringing of my phone. I rubbed my sleepy eyes and looked at the screen—it was Father Pichalakkat.

‘The college yard is teeming with the police,’ he blurted out without preamble. There was no fear or concern in his voice, only amusement. So, his words didn’t upset me. I looked at the wall-clock; it was only getting to 6 a.m.

Before I could speak, he said, ‘Sir, I think it would be better if you didn’t come to college today.’

‘Why?’ I asked evenly.

‘Things may blow up if you come.’

‘How “blow up”? I haven’t done anything wrong. Then why fear?’ I tried to argue without acrimony.

‘Whatever it is, you shouldn’t come to the college today.’ There was an uncharacteristic edge to his voice.

‘Are you worried about the police presence? If they are there, isn’t it for our protection?’

‘I wouldn’t count on it.’ He sounded irascible.

‘Shouldn’t I be present to explain the background and relevance of the question? Shouldn’t we remove their misapprehensions?’

‘It’s not you alone who should do this. We are all there.’

I thought his words made sense. Since I was the question-setter, it would be better if the others in the faculty set up the defence. I had explained everything to Father Pichalakkat and the principal. And they were eloquent enough to impress this upon the interlocutors. Trusting them, I said, ‘If in your opinion, I shouldn’t come to the college, let it be so.’

‘I’ll call you later,’ he said and cut the line.

The next call came almost immediately—Dr Sankararaman, a professor in the physics department, and a close friend of mine. He lived close to the college. His words were full of alarm and concern. Things weren’t looking good. The talk was that the Prophet had been insulted and posters had been stuck on the college walls.

‘The Prophet has been insulted?!’

I was stunned. In the next moment, a flash of lightning seared through my mind. It was the realization that the truncation of P.T. Kunju Muhammed’s name to ‘Muhammed’ was being misinterpreted to create the controversy. I went numb.

‘I had used the name Muhammed in the question paper. Nevertheless, isn’t that a common name? If it were to connote the Prophet’s name, shouldn’t it have been Nabi (Arabic for Prophet and used thus in Malayalam) or Mohammad Nabi?’ My voice was tremulous.

‘All that is true. But if they create this false propaganda, who knows where this will end up?’ He sounded distressed. He rang off saying he would call later.

He called again in a short while. He told me that notices had been distributed in mosques in and around Thodupuzha exhorting the faithful to protest. He also advised me to get in touch with the member of parliament from Idukki, P.T. Thomas, the candidate of the United Democratic Front alliance in which the Muslim League was a constituent.

P.T. Thomas and I have known each other from the time we were teenagers. We have even broken bread together and slept under the same roof. I told him about the controversy and requested him to call the Muslim community leaders in Thodupuzha to remove their misapprehensions and help avoid any untoward incidents.

Then I called K.I. Antony, a local leader in Thodupuzha, and appealed to him to intervene. He had been my colleague in Nirmala College, a professor in the Malayalam department.

The next call that I received was from Thodupuzha Deputy Superintendent of Police K.G. Simon. I narrated the background of the controversial question, and my non-culpability in the whole matter.

After that, there was a call on my landline—an unknown Muslim from Thodupuzha. After hearing the pronouncements in the mosque and exhortations to the community to protest, he had somehow discovered my number and called to find out the truth. I clarified the matter to him and he seemed satisfied.

His parting words were: ‘Thank you, sir. I understand the situation completely. The question now is: How can this be relayed to everybody here? Moreover, there are people in my community hell-bent on fomenting trouble.’

I noticed a cup of black tea that someone had brought to me while I was busy on the telephone. I decided to drink it although it had gone cold. But before I could take a sip the phone rang again. It was a senior professor from the college, who I knew had connections with police officers in Thodupuzha. He advised me to move out of my house and stay away for some time.

‘Do you think someone may attack me?’

‘Not only that, there is also a possibility that the police may arrest you.’

‘Why? What crime have I committed?’

‘Irrespective of that, there is a move to do that.’

‘Where did you get this information, sir? From the police department?’

‘You may consider it so. Anyway, don’t let them arrest you now.’

Excerpted from the book A Thousand Cuts: An Innocent Question and Deadly Answers published by Penguin Random House India with due permission from the publisher and the author and the translator.

Comments are closed.