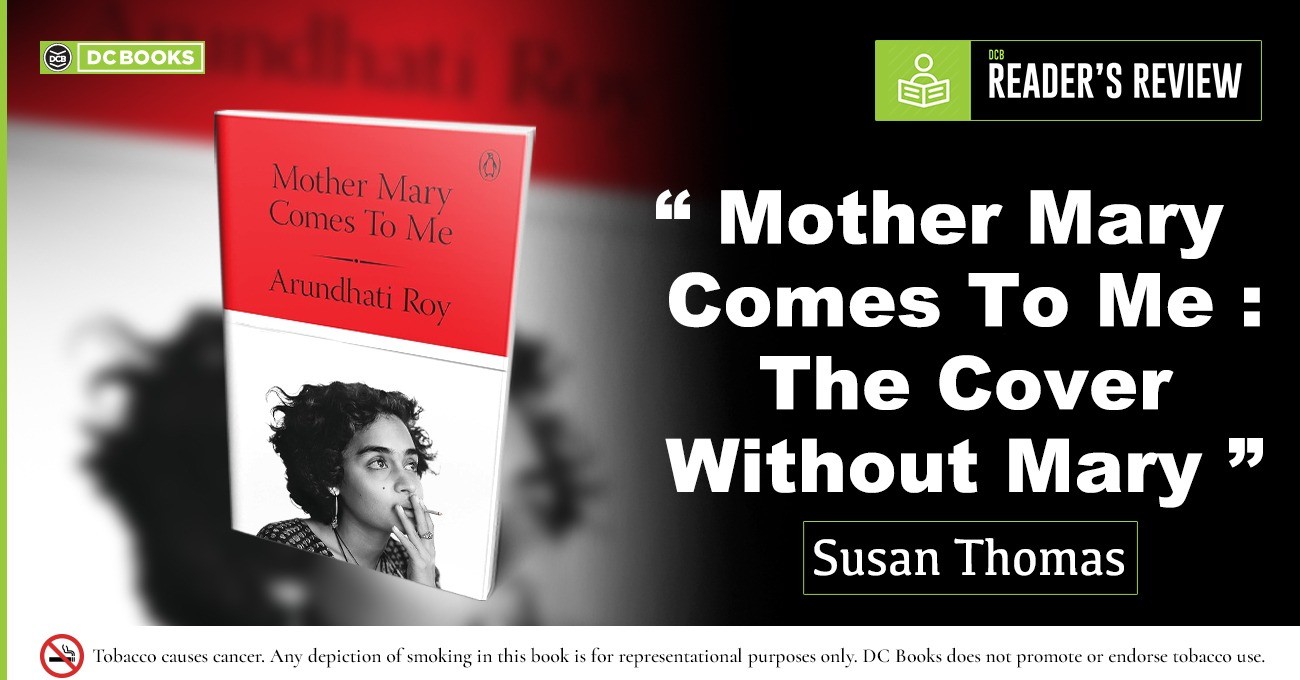

Mother Mary Comes To Me : The Cover Without Mary

Mother Mary Comes To Me: A review by Susan Thomas

WHY MARY WILL NEVER BE ON THE COVER OF

MOTHER MARY COMES TO ME

—SUSAN THOMAS

Arundhati would love a dissenting note. After all, she is the contrarian-in-chief this country loves to love and hate at the same time. The books arrived, gifted by two friends independently, knowing my devotion to her and her first book (both inseparable, which is how it is for many). They were red-bound like the Bishops with sashes at the midriff, announcing their importance in the publishing landscape, worthy of praise and worship, and with a muted but gilded moth presiding over it. When a book comes with two pictures of the author on the dust cover (a younger, edgy one in the front with a lit cigarette and an older, more supple one at the back), you know the prose is less important than the princess of prose, an epithet India Today gave, when they did the cover story on her in 1997. That there was no picture of the titular hero, Mary Roy, inside or outside, seemed deliberate in the power equation. No space will be conceded.

I know countless students who have been tutored by Mr., lawyers who have met her while she fought the landmark case, and casual people who come away blinded by her light after meeting her. When they talk of her, they are like just opened soda—gushing, tingling, and frothy. Once the bubbles settle, they tell you how she can fly off the handle and bruise you. She is no plain vanilla, but a sliver of cinnamon that can be searingly hot and cloyingly sweet. Effective even in small quantities, like a strong spice. I know the countless opinions people have of MR and Pallikkoodam, which sits in Kerala as an elitist edifice today, rechristened from its original name of Corpus Christi. I love that it changed its name, that there was a change of heart and an honest admission of it. Honesty has that quality; it shines through, and that’s exactly what I miss in the new book and the hubbub around it. If I thought this book was about Mary Roy (MR), I was in for a surprise, because MR is on the fringes. Her daughter drags her to the centre of the narrative, pushes her back and forth, and the power struggle is the leitmotif of the book. In doing so, it sometimes becomes a caricature.

Mother Mary Comes To Me is Arundhati making sense of her chaotic life, looking back on why she did what she did, and fortunately, there is a Mother, excellent but eccentric on the edges and now dead, who allows her considerable freedom to pen a life story without the fear of offence and defense. There is the absurdity of privilege being mask-taped to look like trauma, of a hill house in Ooty which only families endowed with considerable wealth and generational standing could afford in the South of India, of being educated in one of the boarding schools there, of meeting Laurie Baker, the legend, who influenced her into taking up architecture as an academic discipline and uncles and aunts—one a Rhodes scholar (she eventually marries another Rhodes scholar), another who gets her free tickets to fly in Air India in the 70s and the cultural capital of a violin playing grandmother, Imperial entomologist for a grandfather and an educated mother with ambition and plans. This is a sophisticated woman, who in her younger years had accepted a national award from the President of India, before evolving into a shape that doubts the State and its judgment. The final act of sophistication was the book release in St Teresa’s College, another monument of old moneyed elitism (full disclosure—I studied there for five years).

Perhaps the greatest skill of Arundhati Roy is the comic relief she provides to desperate situations. It seems a coping mechanism she sharpened while growing up. Her scenes have the clarity of an ace photographer, who fits various lenses on her camera and awards each frame the rightful view it deserves. When that precision combines with quirk, we get absolute gems like cab drivers in Ooty being the best dressed in the country when her grandfather’s suits were handed down to them.

In MMTC, she is on familiar turf, her immediate circle of family and friends, worn like an eternity band, albeit around the middle finger. The God of Small Things forms the framework. And like a rosary, whose beads one thumb in familiar complacency, we can read about the family in MMTC, yet again. The characters comfortably come to life, and I slipped into it with ease. She has filled in the gaps, separated fact from fiction with a finality that no one else can corroborate, defend, or stand up against. She confesses that her dedication to her mother at the beginning of GoST, who loved me enough to let me go, was a piece of fiction. In this book, her dedication says, Mary Roy, who never said let it be. Credibility seems to be in crisis.

Her cleverness lies in the way she wields language – deft, sharp, and precise to deliver an arrangement of words that has a lyrical quality. Yet the book fails to grip me through its rushed narration, through Narmada, through Kashmir valley, through Dandakaranya, without really answering why she does not stay with an issue long enough after drawing attention to it through her prose and popularity, both. If this book is not about MR, then it is not really about Arundhati either because she glosses hurriedly over the most contentious parts of her own life, both public and private. I thus got a half-baked cookie – chewy and raw but posh enough to be carried around. The craft and the structural beauty of God of Small Things, whose many passages I know by heart, seemed absent from the classroom.

Every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way, and this unhappy family seems unhappy because of its unmistakable privilege that seems too difficult to shake off. Her uncomfortable relationship with money, privilege and the need to reconcile her wild child was best told through her own lens than foisting the mother up the cross for all to see her warts and cellulite immersed in a tub, years after she had died. Old age, infirmities, and the minutiae of assisted living, its indignity and helplessness, deserve humanity and tenderness. I know, because my father today lies in a web of tubes and cannulae, and I try and protect his privacy like a guard dog, sniffling through private grief rather than publicly sharing the painful details of palliative care.

To love. To be loved. To never forget your own insignificance…to never simplify what is complicated or complicate what is simple. To respect strength, never power. Above all. to watch. To try and understand. To never look away. And never, never to forget.

– The God of Small Things, Arundhati Roy

The intimate details of a life, of your mother’s life, that you have access to as the daughter, what is the limit of decency you will set, especially when she is no more? There is a reason why it is called trauma porn in the internet in a way. Consent, which seems to have been an important concern for her in the case of Phoolan Devi, seems to be of no consequence when it is her own mother’s life. Here, her mother’s story is something she can take liberty to narrate, as her daughter, no questions asked, although the irony is not lost that she had to un-daughter herself to love her and clinically pen this work.

If humiliation traps and trauma porn sell on the internet today, then a trauma story from Arundhati Roy, a real-life one at that, will grab eyeballs, and all other balls that are there to be grabbed at the sales counter. Arundhati Roy today is a cult, a word she uses to describe the aura around her mercurial mum. She is the Goddess of Big Ticket Things, yet her voice quaked when asked about her choice of publisher. The salt and pepper curls—that sit atop kajal rimmed eyes, signature twinkling nose stud, and an elegant neck that wears different threads of bohemia in different seasons—attract movie stars, activists, writers, housewives, and students who want a slice of the persona today.

Tracing every eccentricity to childhood trauma is a trite trope on the socials. Yet trauma is trauma, even in privileged homes. But in adulthood, at “a viable, disabled age”, when Responsibility knocks on your nose, one reconciles, looks oneself in the eye, and becomes one’s own person rather than looking to charge others with love crimes. Life then is to live with duplicity and contradictions, swathed in self-awareness rather than self-absorption, and everyone should be allowed that, mothers, sons, daughters all.

MMTC is the final round in the power duel, played out after one pugilist is long dead and removed from the ring. Dealing deathly blows to each other seems to be their love language but when the writer is inseparable from the daughter, there is a larger moral question whether art and literature should be told from the standpoint of humanity first. Here, the mother is seen under a reductionist lens that sits contrary to AR’s pronouncements on feminism, bringing out nothing about the visionary woman MR was, who was way, way (double for emphasis) ahead of her times. That she triumphed in Kottayam, in the heart of Central Travancore, amidst the fanatically insular and navel-gazing Syrian Christians, is her greatest feat, unrelenting in demands and charting her own path. It was her act of rebellion, sitting right on their head, refusing to run away, and as poetic justice was served, they came in droves to put their children under her tutelage. MR then picked her fight, stayed with it all her life, nurtured it with her blood and marrow, unlike the daughter, who tastes each fight and leaves the table too soon.

One wished this were a long essay in the Pallikkodam school mag or a lecture AR delivered in its premises, without having to capitalize on a mother’s maniacal genius, minus the publication shenanigans where India’s most famous post-modern symbol of resistance appeared in her carefully constructed careless look and $500 ensemble. There was nothing quiet or intimate about the release of this book, which was calibrated like a time-controlled IV drip that came in trickles to the public vein. And then there was the musical opening, which sat in contrast to the dedication. Performance economy, it is.

We are all walking each other home, they say. This comeback at a parent, long after she is gone and mute like the moth now, is the unsettled adolescent walking the Mother home with a vengeance, down the mottakunnu, complete with a PR team and a painted van in tow, with printed totes that do not bear Mary Roy’s photo but.

Mary will never be on the cover.

Let it be then…

Courtesy

– SUSAN THOMAS